Chinese National Identity under Reconstruction Lin Gang Wu Weixu Shanghai Jiao Tong University Soon after Mao Zedong declared on the stage of Tiananmen that the Chinese people had stood up,it seemed that China had almost finished the process of nation-building,which was stimulated by one hundred years of national humiliation and periodical foreign invasions:the only exception then was Taiwan,which had been under the control of Chinese Nationalists since 1945 Over the past seven decades,there have been two Chinese societies governed by different political regimes across the Taiwan Strait.From the perspective of the Chinese mainland,people living in Taiwan,or the so-called Taiwanese,are of course part of "the Chinese,including the overwhelming majority Han Chinese and tiny aboriginals that are regarded as one of 55 minor ethnicities within the Chinese nation. The growing Taiwanese identity on the island despite peaceful development of cross-strait relations over the past seven years,however,has highlighted the marginal existence of Chinese national identity (guojia rentong)on the island.As more people on Taiwan nowadays identify themselves as Taiwanese,rather than Chinese or both,people in the mainland have worked hard to reconstruct the concept of China through political communication,economic integration,social exchange and cultural assimilation across the Taiwan Strait.New terms such as "two shores,one close family'"(两岸一家亲)and“both sides effecting the Chinese dream”(共圆中国梦)have been created and added into the existed political vocabularies of"a community for two-shores'shared fortune'”(两岸命运共同体),“great rejuvenation of Chinese nation'"(中华民族的伟大复兴),etc. This paper discusses the growing Taiwanese identity on the island and Beijing's efforts to reconstruct Chinese national identity as related to Taiwan.Theoretically,Chinese national identity is both indigenous and reconstructive.The ancient concept of middle kingdom has been enriched continually,thanks to political expansion and cultural assimilation throughout history.From 1949 to 1979,amid political confrontation and military tension,Chinese people in the mainland were educated to liberate miserable people on Taiwan and bring the island back to its motherland.From 1979 on,Taiwan's developmental experience and increasing cross-strait civic exchanges have expanded mainlanders'imagination of modernization and understanding of national identity.Past experience suggests that the reconstruction of Chinese national identity across the Taiwan Strait is contingent upon not only economic modernization and integration,mutual cultural exchange and assimilation,and reinterpretation of contemporary Chinese history and political relations between the two entities prior to China's reunification,but also improvement of public governance and political engineering in the mainland. Taiwanese National Identity on Rise Various survey data have demonstrated the growth of Taiwanese national identity on both cultural/ethnical(minzu)and political/civil dimensions over the past two decades,evidenced by the fact that more Taiwan people nowadays identify themselves as Taiwanese,rather than Chinese or both Chinese and Taiwanese,with clear preference to independence than unification. According to the longitudinal data provided by the Election Study Center (ESC)at National 1

1 Chinese National Identity under Reconstruction Lin Gang & Wu Weixu Shanghai Jiao Tong University Soon after Mao Zedong declared on the stage of Tiananmen that the Chinese people had stood up, it seemed that China had almost finished the process of nation-building,which was stimulated by one hundred years of national humiliation and periodical foreign invasions;the only exception then was Taiwan,which had been under the control of Chinese Nationalists since 1945. Over the past seven decades, there have been two Chinese societies governed by different political regimes across the Taiwan Strait. From the perspective of the Chinese mainland, people living in Taiwan, or the so-called Taiwanese, are of course part of “ the Chinese, ” including the overwhelming majority Han Chinese and tiny aboriginals that are regarded as one of 55 minor ethnicities within the Chinese nation. The growing Taiwanese identity on the island despite peaceful development of cross-strait relations over the past seven years, however, has highlighted the marginal existence of Chinese national identity (guojia rentong) on the island. As more people on Taiwan nowadays identify themselves as Taiwanese, rather than Chinese or both, people in the mainland have worked hard to reconstruct the concept of China through political communication, economic integration, social exchange and cultural assimilation across the Taiwan Strait. New terms such as “two shores, one close family(” 两岸一家亲)and “both sides effecting the Chinese dream(” 共圆中国梦)have been created and added into the existed political vocabularies of “a community for two-shores’ shared fortune”(两岸命运共同体), “great rejuvenation of Chinese nation”(中华民族的伟大复兴),etc. This paper discusses the growing Taiwanese identity on the island and Beijing’s efforts to reconstruct Chinese national identity as related to Taiwan. Theoretically, Chinese national identity is both indigenous and reconstructive. The ancient concept of middle kingdom has been enriched continually, thanks to political expansion and cultural assimilation throughout history. From 1949 to 1979, amid political confrontation and military tension, Chinese people in the mainland were educated to liberate miserable people on Taiwan and bring the island back to its motherland. From 1979 on, Taiwan’s developmental experience and increasing cross-strait civic exchanges have expanded mainlanders’ imagination of modernization and understanding of national identity. Past experience suggests that the reconstruction of Chinese national identity across the Taiwan Strait is contingent upon not only economic modernization and integration, mutual cultural exchange and assimilation, and reinterpretation of contemporary Chinese history and political relations between the two entities prior to China’s reunification, but also improvement of public governance and political engineering in the mainland. Taiwanese National Identity on Rise Various survey data have demonstrated the growth of Taiwanese national identity on both cultural/ethnical (minzu) and political/civil dimensions over the past two decades, evidenced by the fact that more Taiwan people nowadays identify themselves as Taiwanese, rather than Chinese or both Chinese and Taiwanese, with clear preference to independence than unification. According to the longitudinal data provided by the Election Study Center (ESC) at National

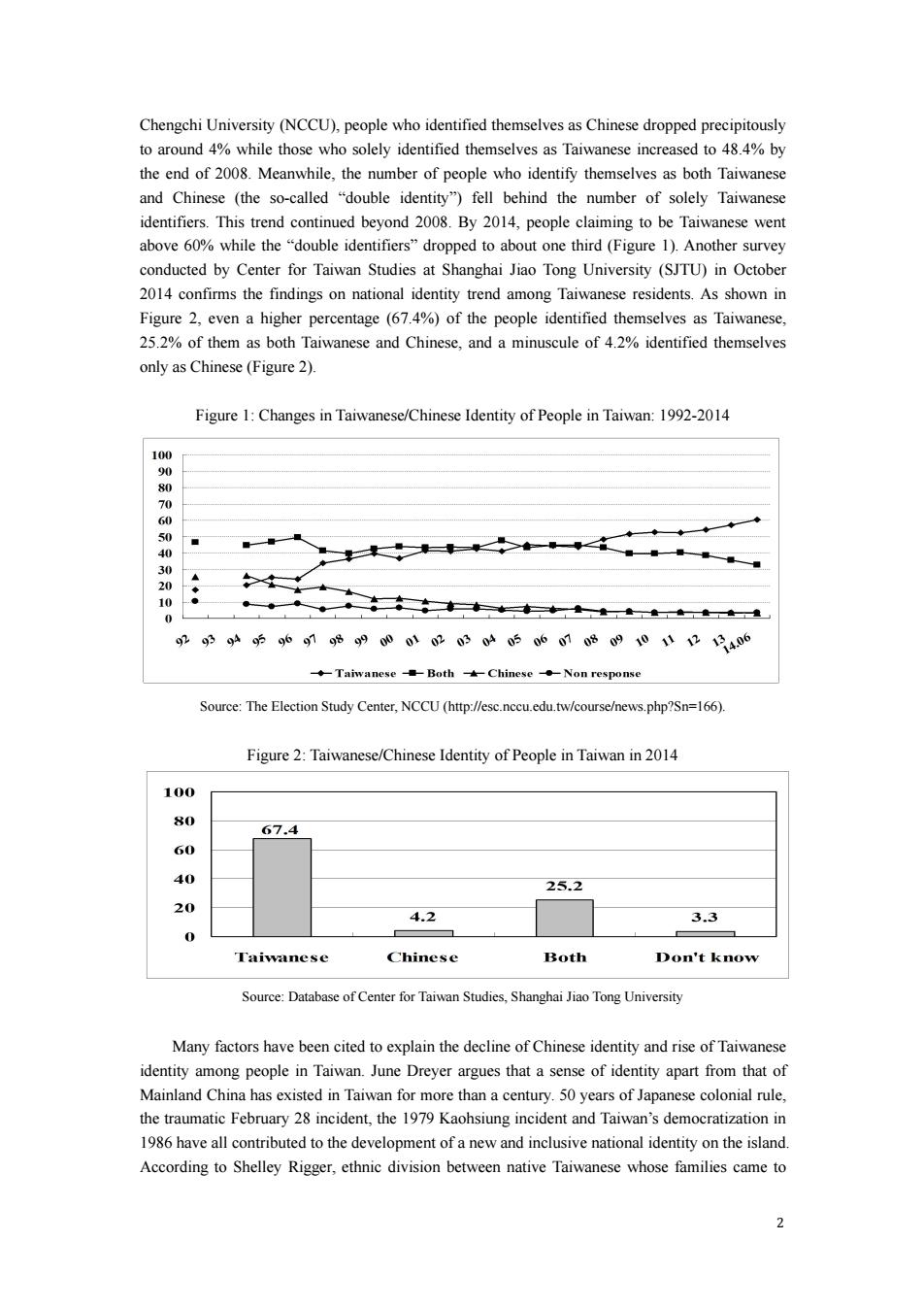

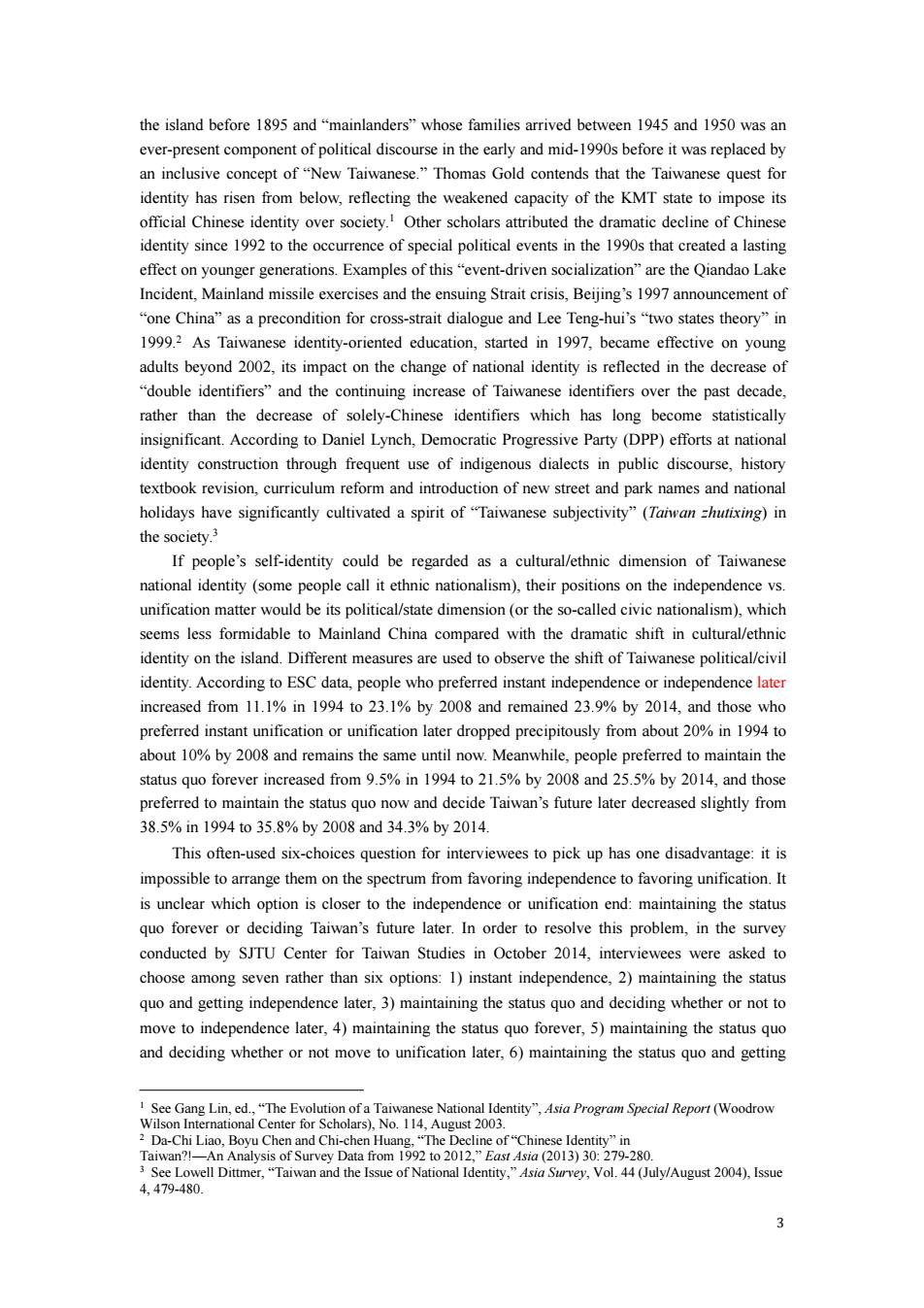

Chengchi University (NCCU),people who identified themselves as Chinese dropped precipitously to around 4%while those who solely identified themselves as Taiwanese increased to 48.4%by the end of 2008.Meanwhile,the number of people who identify themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese (the so-called "double identity")fell behind the number of solely Taiwanese identifiers.This trend continued beyond 2008.By 2014,people claiming to be Taiwanese went above 60%while the "double identifiers"dropped to about one third(Figure 1).Another survey conducted by Center for Taiwan Studies at Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU)in October 2014 confirms the findings on national identity trend among Taiwanese residents.As shown in Figure 2,even a higher percentage(67.4%)of the people identified themselves as Taiwanese, 25.2%of them as both Taiwanese and Chinese,and a minuscule of 4.2%identified themselves only as Chinese(Figure 2). Figure 1:Changes in Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of People in Taiwan:1992-2014 100 90 7 50 3 0 10 0 9294g61%9W0亚B以618四01406 ◆Taiwanese-Both-士Chinese●-Non response Source:The Election Study Center,NCCU (http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/course/news.php?Sn=166). Figure 2:Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of People in Taiwan in 2014 100 80 67.4 60 40 25.2 20 4.2 3.3 Taiwanese Chinese Both Don't know Source:Database of Center for Taiwan Studies,Shanghai Jiao Tong University Many factors have been cited to explain the decline of Chinese identity and rise of Taiwanese identity among people in Taiwan.June Dreyer argues that a sense of identity apart from that of Mainland China has existed in Taiwan for more than a century.50 years of Japanese colonial rule, the traumatic February 28 incident,the 1979 Kaohsiung incident and Taiwan's democratization in 1986 have all contributed to the development of a new and inclusive national identity on the island. According to Shelley Rigger,ethnic division between native Taiwanese whose families came to 2

2 Chengchi University (NCCU), people who identified themselves as Chinese dropped precipitously to around 4% while those who solely identified themselves as Taiwanese increased to 48.4% by the end of 2008. Meanwhile, the number of people who identify themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese (the so-called “double identity”) fell behind the number of solely Taiwanese identifiers. This trend continued beyond 2008. By 2014, people claiming to be Taiwanese went above 60% while the “double identifiers” dropped to about one third (Figure 1). Another survey conducted by Center for Taiwan Studies at Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU) in October 2014 confirms the findings on national identity trend among Taiwanese residents. As shown in Figure 2, even a higher percentage (67.4%) of the people identified themselves as Taiwanese, 25.2% of them as both Taiwanese and Chinese, and a minuscule of 4.2% identified themselves only as Chinese (Figure 2). Figure 1: Changes in Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of People in Taiwan: 1992-2014 Source: The Election Study Center, NCCU (http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/course/news.php?Sn=166). Figure 2: Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of People in Taiwan in 2014 Source: Database of Center for Taiwan Studies, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Many factors have been cited to explain the decline of Chinese identity and rise of Taiwanese identity among people in Taiwan. June Dreyer argues that a sense of identity apart from that of Mainland China has existed in Taiwan for more than a century. 50 years of Japanese colonial rule, the traumatic February 28 incident, the 1979 Kaohsiung incident and Taiwan’s democratization in 1986 have all contributed to the development of a new and inclusive national identity on the island. According to Shelley Rigger, ethnic division between native Taiwanese whose families came to

the island before 1895 and "mainlanders"whose families arrived between 1945 and 1950 was an ever-present component of political discourse in the early and mid-1990s before it was replaced by an inclusive concept of"New Taiwanese."Thomas Gold contends that the Taiwanese quest for identity has risen from below,reflecting the weakened capacity of the KMT state to impose its official Chinese identity over society.Other scholars attributed the dramatic decline of Chinese identity since 1992 to the occurrence of special political events in the 1990s that created a lasting effect on younger generations.Examples of this"event-driven socialization"are the Qiandao Lake Incident,Mainland missile exercises and the ensuing Strait crisis,Beijing's 1997 announcement of "one China"as a precondition for cross-strait dialogue and Lee Teng-hui's "two states theory"in 1999.2 As Taiwanese identity-oriented education,started in 1997,became effective on young adults beyond 2002,its impact on the change of national identity is reflected in the decrease of "double identifiers"and the continuing increase of Taiwanese identifiers over the past decade, rather than the decrease of solely-Chinese identifiers which has long become statistically insignificant.According to Daniel Lynch,Democratic Progressive Party(DPP)efforts at national identity construction through frequent use of indigenous dialects in public discourse,history textbook revision,curriculum reform and introduction of new street and park names and national holidays have significantly cultivated a spirit of "Taiwanese subjectivity"(Taiwan zhutixing)in the society.3 If people's self-identity could be regarded as a cultural/ethnic dimension of Taiwanese national identity (some people call it ethnic nationalism),their positions on the independence vs. unification matter would be its political/state dimension (or the so-called civic nationalism).which seems less formidable to Mainland China compared with the dramatic shift in cultural/ethnic identity on the island.Different measures are used to observe the shift of Taiwanese political/civil identity.According to ESC data,people who preferred instant independence or independence later increased from 11.1%in 1994 to 23.1%by 2008 and remained 23.9%by 2014,and those who preferred instant unification or unification later dropped precipitously from about 20%in 1994 to about 10%by 2008 and remains the same until now.Meanwhile,people preferred to maintain the status quo forever increased from 9.5%in 1994 to 21.5%by 2008 and 25.5%by 2014,and those preferred to maintain the status quo now and decide Taiwan's future later decreased slightly from 38.5%in1994to35.8%by2008and34.3%by2014. This often-used six-choices question for interviewees to pick up has one disadvantage:it is impossible to arrange them on the spectrum from favoring independence to favoring unification.It is unclear which option is closer to the independence or unification end:maintaining the status quo forever or deciding Taiwan's future later.In order to resolve this problem,in the survey conducted by SJTU Center for Taiwan Studies in October 2014,interviewees were asked to choose among seven rather than six options:1)instant independence,2)maintaining the status quo and getting independence later,3)maintaining the status quo and deciding whether or not to move to independence later,4)maintaining the status quo forever,5)maintaining the status quo and deciding whether or not move to unification later,6)maintaining the status quo and getting See Gang Lin,ed.,"The Evolution ofa Taiwanese National Identity",Asia Program Special Report (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars),No.114,August 2003. 2 Da-Chi Liao,Boyu Chen and Chi-chen Huang,"The Decline of"Chinese Identity"in Taiwan?!-An Analysis of Survey Data from 1992 to 2012,"East Asia(2013)30:279-280. 3 See Lowell Dittmer,"Taiwan and the Issue of National Identity,"Asia Survey,Vol.44(July/August 2004),Issue 4,479-480. 3

3 the island before 1895 and “mainlanders” whose families arrived between 1945 and 1950 was an ever-present component of political discourse in the early and mid-1990s before it was replaced by an inclusive concept of “New Taiwanese.” Thomas Gold contends that the Taiwanese quest for identity has risen from below, reflecting the weakened capacity of the KMT state to impose its official Chinese identity over society.1 Other scholars attributed the dramatic decline of Chinese identity since 1992 to the occurrence of special political events in the 1990s that created a lasting effect on younger generations. Examples of this “event-driven socialization” are the Qiandao Lake Incident, Mainland missile exercises and the ensuing Strait crisis, Beijing’s 1997 announcement of “one China” as a precondition for cross-strait dialogue and Lee Teng-hui’s “two states theory” in 1999.2 As Taiwanese identity-oriented education, started in 1997, became effective on young adults beyond 2002, its impact on the change of national identity is reflected in the decrease of “double identifiers” and the continuing increase of Taiwanese identifiers over the past decade, rather than the decrease of solely-Chinese identifiers which has long become statistically insignificant. According to Daniel Lynch, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) efforts at national identity construction through frequent use of indigenous dialects in public discourse, history textbook revision, curriculum reform and introduction of new street and park names and national holidays have significantly cultivated a spirit of “Taiwanese subjectivity” (Taiwan zhutixing) in the society.3 If people’s self-identity could be regarded as a cultural/ethnic dimension of Taiwanese national identity (some people call it ethnic nationalism), their positions on the independence vs. unification matter would be its political/state dimension (or the so-called civic nationalism), which seems less formidable to Mainland China compared with the dramatic shift in cultural/ethnic identity on the island. Different measures are used to observe the shift of Taiwanese political/civil identity. According to ESC data, people who preferred instant independence or independence later increased from 11.1% in 1994 to 23.1% by 2008 and remained 23.9% by 2014, and those who preferred instant unification or unification later dropped precipitously from about 20% in 1994 to about 10% by 2008 and remains the same until now. Meanwhile, people preferred to maintain the status quo forever increased from 9.5% in 1994 to 21.5% by 2008 and 25.5% by 2014, and those preferred to maintain the status quo now and decide Taiwan’s future later decreased slightly from 38.5% in 1994 to 35.8% by 2008 and 34.3% by 2014. This often-used six-choices question for interviewees to pick up has one disadvantage: it is impossible to arrange them on the spectrum from favoring independence to favoring unification. It is unclear which option is closer to the independence or unification end: maintaining the status quo forever or deciding Taiwan’s future later. In order to resolve this problem, in the survey conducted by SJTU Center for Taiwan Studies in October 2014, interviewees were asked to choose among seven rather than six options: 1) instant independence, 2) maintaining the status quo and getting independence later, 3) maintaining the status quo and deciding whether or not to move to independence later, 4) maintaining the status quo forever, 5) maintaining the status quo and deciding whether or not move to unification later, 6) maintaining the status quo and getting 1 See Gang Lin, ed., “The Evolution of a Taiwanese National Identity”, Asia Program Special Report (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars), No. 114, August 2003. 2 Da-Chi Liao, Boyu Chen and Chi-chen Huang, “The Decline of “Chinese Identity” in Taiwan?!—An Analysis of Survey Data from 1992 to 2012,” East Asia (2013) 30: 279-280. 3 See Lowell Dittmer, “Taiwan and the Issue of National Identity,” Asia Survey, Vol. 44 (July/August 2004), Issue 4, 479-480

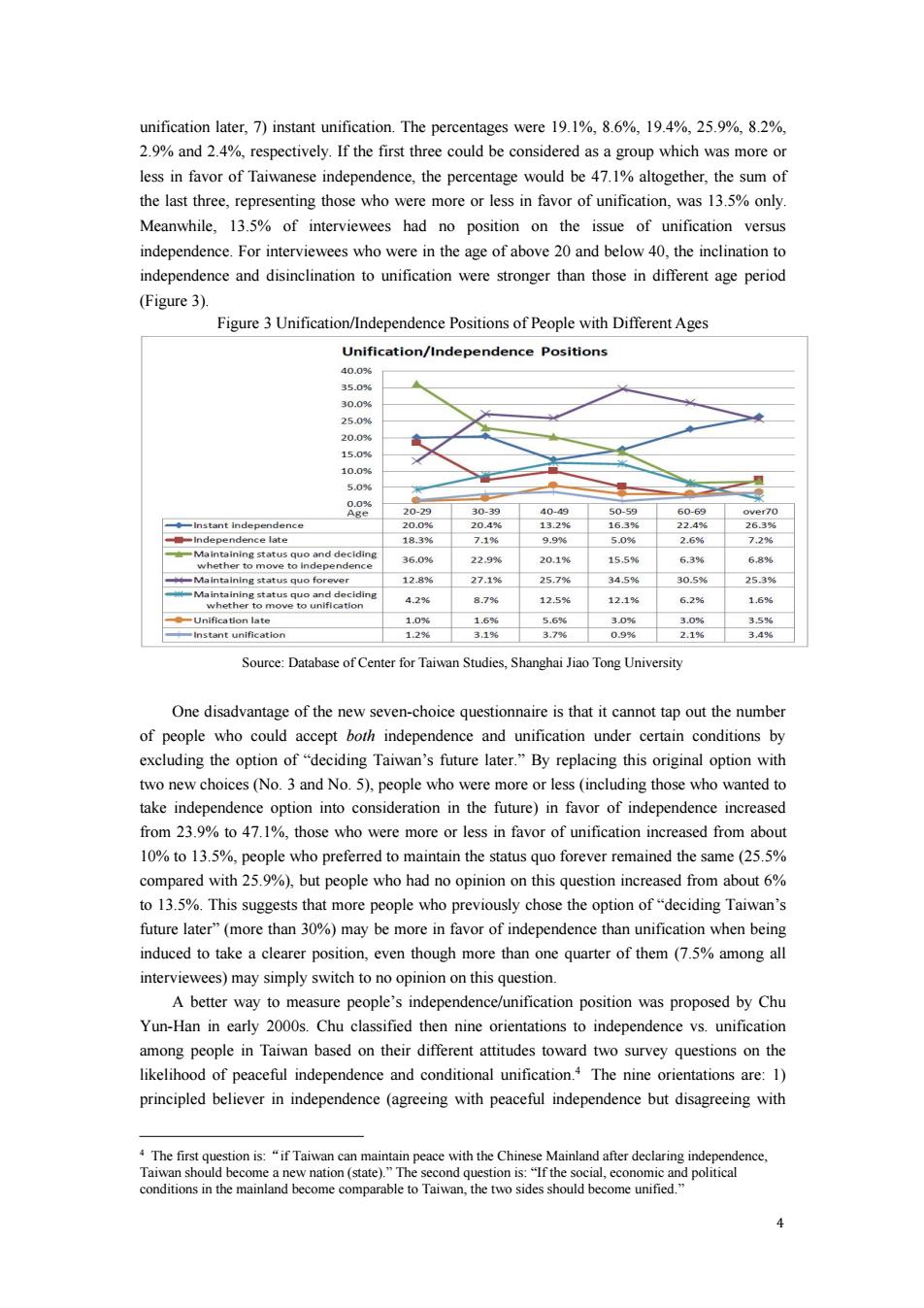

unification later,7)instant unification.The percentages were 19.1%,8.6%,19.4%,25.9%,8.2%, 2.9%and 2.4%,respectively.If the first three could be considered as a group which was more or less in favor of Taiwanese independence,the percentage would be 47.1%altogether,the sum of the last three,representing those who were more or less in favor of unification,was 13.5%only. Meanwhile,13.5%of interviewees had no position on the issue of unification versus independence.For interviewees who were in the age of above 20 and below 40,the inclination to independence and disinclination to unification were stronger than those in different age period (Figure 3). Figure 3 Unification/Independence Positions of People with Different Ages Unification/Independence Positions 40.0% 35.0% 30.0% 25.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 0.0% Age 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 over70 Instant independence 20.0% 20.496 13:296 16.39% 22.4% 263% Independence late 18.3% 7.1% 9.9% 5.0% 2.6% 7,2% Maintaining status quo and deciding 36.0% 22.9% 20.1% 15.5% 63% 6,8% whether to move to independence .Maintaining status quo forever 12.8% 27.1% 25.7% 34.5% 30.5% 253% Maintaining status quo and deciding whether to move to unification 4.2% 8.7% 12.5% 12.1% 6.2% 1.6% .Unification late 1.0% 1.6% 5.6% 3.0% 3.0% 35% Instant unification 1.2% 31% 3.7% 09% 2.1% 34% Source:Database of Center for Taiwan Studies,Shanghai Jiao Tong University One disadvantage of the new seven-choice questionnaire is that it cannot tap out the number of people who could accept both independence and unification under certain conditions by excluding the option of"deciding Taiwan's future later."By replacing this original option with two new choices (No.3 and No.5),people who were more or less (including those who wanted to take independence option into consideration in the future)in favor of independence increased from 23.9%to 47.1%,those who were more or less in favor of unification increased from about 10%to 13.5%,people who preferred to maintain the status quo forever remained the same(25.5% compared with 25.9%),but people who had no opinion on this question increased from about 6% to 13.5%.This suggests that more people who previously chose the option of"deciding Taiwan's future later"(more than 30%)may be more in favor of independence than unification when being induced to take a clearer position,even though more than one quarter of them(7.5%among all interviewees)may simply switch to no opinion on this question. A better way to measure people's independence/unification position was proposed by Chu Yun-Han in early 2000s.Chu classified then nine orientations to independence vs.unification among people in Taiwan based on their different attitudes toward two survey questions on the likelihood of peaceful independence and conditional unification.The nine orientations are:1) principled believer in independence (agreeing with peaceful independence but disagreeing with 4 The first question is:"if Taiwan can maintain peace with the Chinese Mainland after declaring independence, Taiwan should become a new nation (state)."The second question is:"If the social,economic and political conditions in the mainland become comparable to Taiwan,the two sides should become unified." 4

4 unification later, 7) instant unification. The percentages were 19.1%, 8.6%, 19.4%, 25.9%, 8.2%, 2.9% and 2.4%, respectively. If the first three could be considered as a group which was more or less in favor of Taiwanese independence, the percentage would be 47.1% altogether, the sum of the last three, representing those who were more or less in favor of unification, was 13.5% only. Meanwhile, 13.5% of interviewees had no position on the issue of unification versus independence. For interviewees who were in the age of above 20 and below 40, the inclination to independence and disinclination to unification were stronger than those in different age period (Figure 3). Figure 3 Unification/Independence Positions of People with Different Ages Source: Database of Center for Taiwan Studies, Shanghai Jiao Tong University One disadvantage of the new seven-choice questionnaire is that it cannot tap out the number of people who could accept both independence and unification under certain conditions by excluding the option of “deciding Taiwan’s future later.” By replacing this original option with two new choices (No. 3 and No. 5), people who were more or less (including those who wanted to take independence option into consideration in the future) in favor of independence increased from 23.9% to 47.1%, those who were more or less in favor of unification increased from about 10% to 13.5%, people who preferred to maintain the status quo forever remained the same (25.5% compared with 25.9%), but people who had no opinion on this question increased from about 6% to 13.5%. This suggests that more people who previously chose the option of “deciding Taiwan’s future later” (more than 30%) may be more in favor of independence than unification when being induced to take a clearer position, even though more than one quarter of them (7.5% among all interviewees) may simply switch to no opinion on this question. A better way to measure people’s independence/unification position was proposed by Chu Yun-Han in early 2000s. Chu classified then nine orientations to independence vs. unification among people in Taiwan based on their different attitudes toward two survey questions on the likelihood of peaceful independence and conditional unification.4 The nine orientations are: 1) principled believer in independence (agreeing with peaceful independence but disagreeing with 4 The first question is:“if Taiwan can maintain peace with the Chinese Mainland after declaring independence, Taiwan should become a new nation (state).” The second question is: “If the social, economic and political conditions in the mainland become comparable to Taiwan, the two sides should become unified

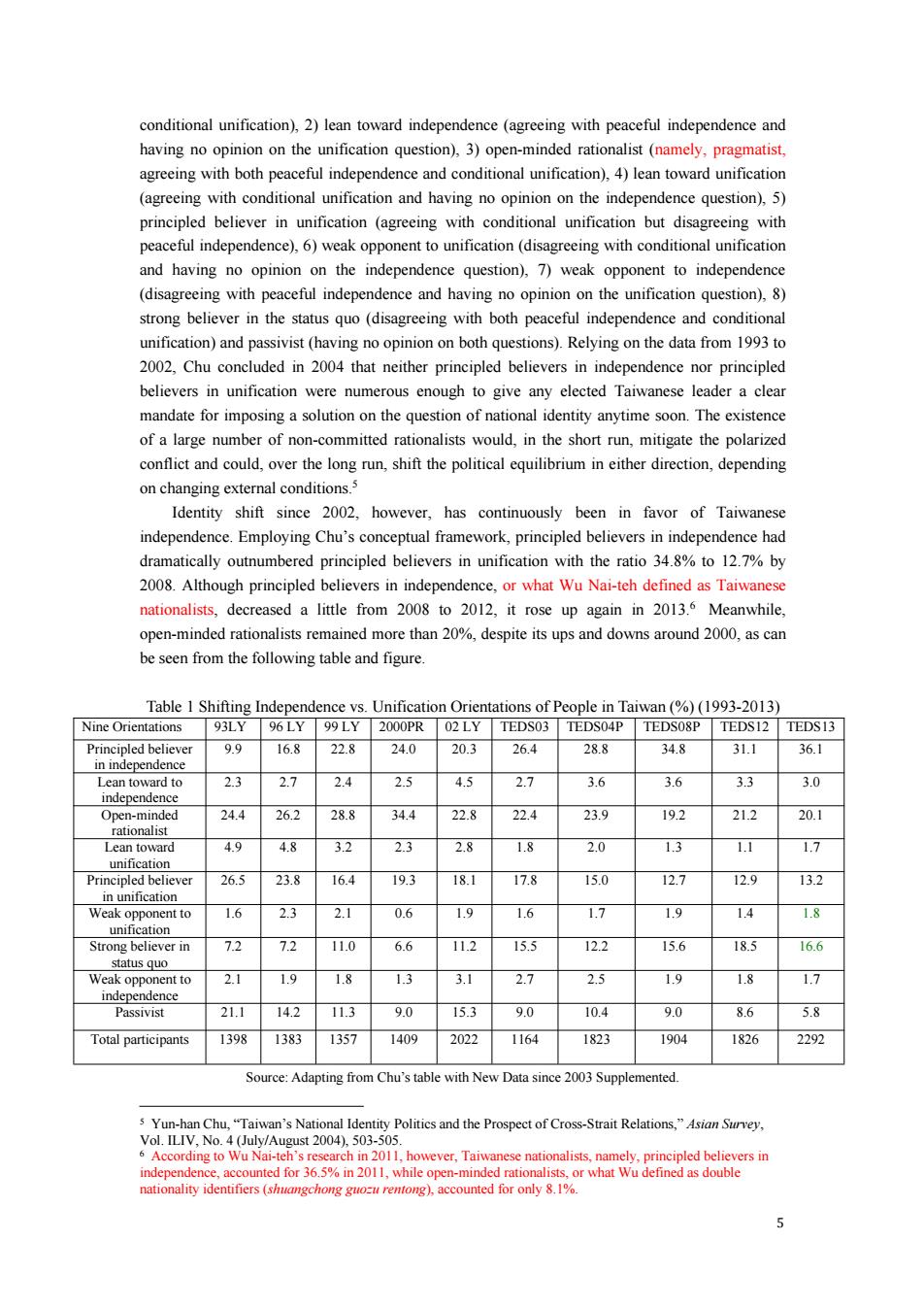

conditional unification),2)lean toward independence (agreeing with peaceful independence and having no opinion on the unification question),3)open-minded rationalist (namely,pragmatist, agreeing with both peaceful independence and conditional unification),4)lean toward unification (agreeing with conditional unification and having no opinion on the independence question),5) principled believer in unification (agreeing with conditional unification but disagreeing with peaceful independence),6)weak opponent to unification(disagreeing with conditional unification and having no opinion on the independence question),7)weak opponent to independence (disagreeing with peaceful independence and having no opinion on the unification question),8) strong believer in the status quo(disagreeing with both peaceful independence and conditional unification)and passivist(having no opinion on both questions).Relying on the data from 1993 to 2002,Chu concluded in 2004 that neither principled believers in independence nor principled believers in unification were numerous enough to give any elected Taiwanese leader a clear mandate for imposing a solution on the question of national identity anytime soon.The existence of a large number of non-committed rationalists would,in the short run,mitigate the polarized conflict and could,over the long run,shift the political equilibrium in either direction,depending on changing external conditions.5 Identity shift since 2002,however,has continuously been in favor of Taiwanese independence.Employing Chu's conceptual framework,principled believers in independence had dramatically outnumbered principled believers in unification with the ratio 34.8%to 12.7%by 2008.Although principled believers in independence,or what Wu Nai-teh defined as Taiwanese nationalists,decreased a little from 2008 to 2012,it rose up again in 2013.6 Meanwhile, open-minded rationalists remained more than 20%,despite its ups and downs around 2000,as can be seen from the following table and figure. Table 1 Shifting Independence vs.Unification Orientations of People in Taiwan(%)(1993-2013) Nine Orientations 93LY 96 LY 99 LY 2000PR 02LY TEDS03 TEDS04P TEDS08P TEDS12 TEDS13 Principled believer 9.9 16.8 22.8 24.0 20.3 26.4 28.8 34.8 31.1 36.1 in independence Lean toward to 2.3 2.7 2.4 2.5 4.5 2.7 3.6 3.6 3.3 3.0 independence Open-minded 24.4 26.2 28.8 34.4 22.8 22.4 23.9 19.2 21.2 20.1 rationalist Lean toward 4.9 4.8 3.2 2.3 2.8 1.8 2.0 1.3 1.1 1.7 unification Principled believer 26.5 23.8 16.4 19.3 18.1 17.8 15.0 12.7 12.9 13.2 in unification Weak opponent to 1.6 2.3 2.1 0.6 1.9 1.6 1.7 1.9 1.4 1.8 unification Strong believer in 7.2 7.2 11.0 6.6 11.2 15.5 12.2 15.6 18.5 16.6 status quo Weak opponent to 2.1 1.9 1.8 1.3 3.1 2.7 2.5 1.9 1.8 1.7 independence Passivist 21.1 14.2 11.3 9.0 15.3 9.0 10.4 9.0 8.6 5.8 Total participants 1398 1383 1357 1409 2022 1164 1823 1904 1826 2292 Source:Adapting from Chu's table with New Data since 2003 Supplemented. s Yun-han Chu,Taiwan's National Identity Politics and the Prospect of Cross-Strait Relations,"Asian Survey, Vol.ILIV,No.4 (July/August 2004).503-505. 6According to Wu Nai-teh's research in 2011,however,Taiwanese nationalists,namely,principled believers in independence,accounted for 36.5%in 2011,while open-minded rationalists,or what Wu defined as double nationality identifiers (shuangchong guozu rentong),accounted for only 8.1%. 5

5 conditional unification), 2) lean toward independence (agreeing with peaceful independence and having no opinion on the unification question), 3) open-minded rationalist (namely, pragmatist, agreeing with both peaceful independence and conditional unification), 4) lean toward unification (agreeing with conditional unification and having no opinion on the independence question), 5) principled believer in unification (agreeing with conditional unification but disagreeing with peaceful independence), 6) weak opponent to unification (disagreeing with conditional unification and having no opinion on the independence question), 7) weak opponent to independence (disagreeing with peaceful independence and having no opinion on the unification question), 8) strong believer in the status quo (disagreeing with both peaceful independence and conditional unification) and passivist (having no opinion on both questions). Relying on the data from 1993 to 2002, Chu concluded in 2004 that neither principled believers in independence nor principled believers in unification were numerous enough to give any elected Taiwanese leader a clear mandate for imposing a solution on the question of national identity anytime soon. The existence of a large number of non-committed rationalists would, in the short run, mitigate the polarized conflict and could, over the long run, shift the political equilibrium in either direction, depending on changing external conditions.5 Identity shift since 2002, however, has continuously been in favor of Taiwanese independence. Employing Chu’s conceptual framework, principled believers in independence had dramatically outnumbered principled believers in unification with the ratio 34.8% to 12.7% by 2008. Although principled believers in independence, or what Wu Nai-teh defined as Taiwanese nationalists, decreased a little from 2008 to 2012, it rose up again in 2013.6 Meanwhile, open-minded rationalists remained more than 20%, despite its ups and downs around 2000, as can be seen from the following table and figure. Table 1 Shifting Independence vs. Unification Orientations of People in Taiwan (%) (1993-2013) Nine Orientations 93LY 96 LY 99 LY 2000PR 02 LY TEDS03 TEDS04P TEDS08P TEDS12 TEDS13 Principled believer in independence 9.9 16.8 22.8 24.0 20.3 26.4 28.8 34.8 31.1 36.1 Lean toward to independence 2.3 2.7 2.4 2.5 4.5 2.7 3.6 3.6 3.3 3.0 Open-minded rationalist 24.4 26.2 28.8 34.4 22.8 22.4 23.9 19.2 21.2 20.1 Lean toward unification 4.9 4.8 3.2 2.3 2.8 1.8 2.0 1.3 1.1 1.7 Principled believer in unification 26.5 23.8 16.4 19.3 18.1 17.8 15.0 12.7 12.9 13.2 Weak opponent to unification 1.6 2.3 2.1 0.6 1.9 1.6 1.7 1.9 1.4 1.8 Strong believer in status quo 7.2 7.2 11.0 6.6 11.2 15.5 12.2 15.6 18.5 16.6 Weak opponent to independence 2.1 1.9 1.8 1.3 3.1 2.7 2.5 1.9 1.8 1.7 Passivist 21.1 14.2 11.3 9.0 15.3 9.0 10.4 9.0 8.6 5.8 Total participants 1398 1383 1357 1409 2022 1164 1823 1904 1826 2292 Source: Adapting from Chu’s table with New Data since 2003 Supplemented. 5 Yun-han Chu, “Taiwan’s National Identity Politics and the Prospect of Cross-Strait Relations,” Asian Survey, Vol. ILIV, No. 4 (July/August 2004), 503-505. 6 According to Wu Nai-teh’s research in 2011, however, Taiwanese nationalists, namely, principled believers in independence, accounted for 36.5% in 2011, while open-minded rationalists, or what Wu defined as double nationality identifiers (shuangchong guozu rentong), accounted for only 8.1%

Figure 4 Shifting Independence vs.Unification Orientations of People in Taiwan(1993-2013) 40 30 20 10 1993 1996 19992000 2002 2003 20042008 20122013 Principled believer in independence ALean toward to independence Open-minded rationalists Lean toward unification Principled believer in unification Weak opponent to unification Strong believer in status quo Weak opponent to independence Passivists From the above table,it can also be seen that the percentage of people who can accept unification under favorable conditions (Line 3,4 and 5)also decreased from 55.8%in 1993 (and 56%in 2000)to 33.2%in 2008 and bounced back a little to 35%in 2013.This suggests,however, more than one-thirds of people in Taiwan still maintain Chinese national identity in the political dimension.The above-mentioned SJTU October 2014 survey data confirmed that 35.3%of interviewees supported unification if the mainland could practice the same political system as Taiwan,while 50.2%of them still rejected unification under this circumstance.The reject rates were even higher comparatively in other surveys.As it can be calculated from Table 1 (line 1,6, and7),the percentage for2004,2008,2012,and2013was42.7%,52.3%,51.2%and54.5%, respectively.Meanwhile,the percentage of people with Taiwanese identity during the same survey in these years was 45.8%,53.1%,57.3%and 57.5%,respectively.The gap between Taiwanese self-identity and desire of not being unified with Chinese mainland is quite marginal.Moreover, the percentage of people who can accept peaceful independence(line 1-3 in Table 1)in the 2004, 2008,2012 and 2013 surveys was 56.3%,57.6%,55.6%and 59.2%.These figures are summarized in the following table. Table 2 Taiwanese Identity and Independence vs.Unification Orientations 2004 2008 2012 2013 Mean Taiwanese identity 45.8% 53.1% 57.3% 57.5% 53.4 Rejecting conditional unification 42.7% 52.3% 51.2% 54.5% 50.2 Accepting peaceful independence 56.3% 57.6% 55.6% 59.2% 57.2 6

6 Figure 4 Shifting Independence vs. Unification Orientations of People in Taiwan (1993-2013) From the above table, it can also be seen that the percentage of people who can accept unification under favorable conditions (Line 3, 4 and 5) also decreased from 55.8% in 1993 (and 56% in 2000) to 33.2% in 2008 and bounced back a little to 35% in 2013. This suggests, however, more than one-thirds of people in Taiwan still maintain Chinese national identity in the political dimension. The above-mentioned SJTU October 2014 survey data confirmed that 35.3% of interviewees supported unification if the mainland could practice the same political system as Taiwan, while 50.2% of them still rejected unification under this circumstance. The reject rates were even higher comparatively in other surveys. As it can be calculated from Table 1 (line 1, 6, and 7), the percentage for 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2013 was 42.7%, 52.3%, 51.2% and 54.5%, respectively. Meanwhile, the percentage of people with Taiwanese identity during the same survey in these years was 45.8%, 53.1%, 57.3% and 57.5%, respectively. The gap between Taiwanese self-identity and desire of not being unified with Chinese mainland is quite marginal. Moreover, the percentage of people who can accept peaceful independence (line 1-3 in Table 1) in the 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2013 surveys was 56.3%, 57.6%, 55.6% and 59.2%. These figures are summarized in the following table. Table 2 Taiwanese Identity and Independence vs. Unification Orientations 2004 2008 2012 2013 Mean Taiwanese identity 45.8% 53.1% 57.3% 57.5% 53.4 Rejecting conditional unification 42.7% 52.3% 51.2% 54.5% 50.2 Accepting peaceful independence 56.3% 57.6% 55.6% 59.2% 57.2

This is greatly different from the situation in the late 1990s and early 2000s when more people in Taiwan had double identities than those with sole Chinese or Taiwanese identity,and more people agreed with unification with the mainland under favorable conditions than those opposed to this option.According to Liu Yi-chou,while about 70.5%of interviewees identified themselves as part of Chinese in the late 1990s,74.5%of interviewees wanted to self-decide the future of Taiwan,revealing the inconsistency between cultural and political dimensions of national identity.In particular,38.1%of interviewees considered Taiwan as part of China and people in Taiwan as part of "the Chinese",but still wanted to self-decide the future of Taiwan.7 As Chiang Yi-hua pointed out in his early work Liberalism,Nationalism and National Identity,as long as cultural and ethnic identity played a key role in national identity,people were not expected to have a clear concept of statehood.Even though one hundred years of separation of Taiwan from the mainland had prepared a base for an independent statehood,it still could not replace the long memory of the two sides as the same country,and different generations in Taiwan were divided on this matter.According to Chiang,the common language,similar religions,overlapping historical memory,geographic closeness and economic division of labor of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait were advantageous conditions for future unification,and political institutions were key factors in shaping the future relations between the two sides.8 It should be recognized that even though most people in Taiwan now only identity themselves as Taiwanese,close to one third of the population have not given up their Chinese (hongguoren)identity.It means that Taiwan is still a divided society when it comes to the basic concept of national identity.Moreover,among people who solely identified themselves as Taiwanese,59.6%of them considered themselves as part of the Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu) and 15.8%of them thought they were both part of the Chinese nation and Chinese(zhongguoren), when being asked to answer the question from blood and cultural perspective.This suggests that concepts of Taiwanese and the Chinese nation could be highly overlapped in a certain sense. While 45.1%of people who identified as Taiwanese understood the concept from historical and cultural perspective,43.7%of them thought Taiwanese mainly meant those who lived and worked in Taiwan.36.3%of Taiwan identifiers could accept the idea of "one China with different interpretations"in dealing with the mainland,and only 46.5%of them disagreed.In other words, only about one-thirds of all interviewees (45.1%X 67.4%=30.4%)identify themselves as Taiwanese and understand the concept from blood or historical and cultural aspects.Among this group of people,38.2%preferred instant or later independence in the SJTU October 2014 survey.10 It seems reasonable to regard 11.6%of people (67.4%X 45.1%X 38.2%=11.6%)in Taiwan as core elements of Taiwanese nationalists.However,16.8%of this small group of people can still accept unification with the Mainland under favorable conditions(democracy). People who identified as Taiwanese seemed to have a clearer understanding of the national identity issue from political/civil/state aspects.For example,77.3%of them disagreed that the people of the Republic of China(ROC)were also Chinese,even when they were reminded that China could be the short name of the ROC (zhongguo as the short name of zhonghua minguo),and only 15%of them agreed that people living in the ROC were also Chinese.Moreover,79%of 7 Liu Yi-chou,"National Identity of People in Taiwan-A New Measurement Way,"Paper delivered at the 1998 annual meeting of Association of Chinese Political Science(Taiwan),January 14,1998,Taipei. 8 Chiang Yi-hua,Liberalism,Nationalism and National Identity (Taipei:Yangchi Cultural Press,1998),217-222. Yang Zhong&Yana Zuo,"Explaining National Identity Shift in Taiwan"(Manuscript). 0 Database of Center for Taiwan Studies,Shanghai Jiao Tong University. 7

7 This is greatly different from the situation in the late 1990s and early 2000s when more people in Taiwan had double identities than those with sole Chinese or Taiwanese identity, and more people agreed with unification with the mainland under favorable conditions than those opposed to this option. According to Liu Yi-chou, while about 70.5% of interviewees identified themselves as part of Chinese in the late 1990s, 74.5% of interviewees wanted to self-decide the future of Taiwan, revealing the inconsistency between cultural and political dimensions of national identity. In particular, 38.1% of interviewees considered Taiwan as part of China and people in Taiwan as part of “the Chinese”, but still wanted to self-decide the future of Taiwan.7 As Chiang Yi-hua pointed out in his early work Liberalism, Nationalism and National Identity, as long as cultural and ethnic identity played a key role in national identity, people were not expected to have a clear concept of statehood. Even though one hundred years of separation of Taiwan from the mainland had prepared a base for an independent statehood, it still could not replace the long memory of the two sides as the same country, and different generations in Taiwan were divided on this matter. According to Chiang, the common language, similar religions, overlapping historical memory, geographic closeness and economic division of labor of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait were advantageous conditions for future unification, and political institutions were key factors in shaping the future relations between the two sides.8 It should be recognized that even though most people in Taiwan now only identity themselves as Taiwanese, close to one third of the population have not given up their Chinese (zhongguoren) identity. It means that Taiwan is still a divided society when it comes to the basic concept of national identity.9 Moreover, among people who solely identified themselves as Taiwanese, 59.6% of them considered themselves as part of the Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu) and 15.8% of them thought they were both part of the Chinese nation and Chinese (zhongguoren), when being asked to answer the question from blood and cultural perspective. This suggests that concepts of Taiwanese and the Chinese nation could be highly overlapped in a certain sense. While 45.1% of people who identified as Taiwanese understood the concept from historical and cultural perspective, 43.7% of them thought Taiwanese mainly meant those who lived and worked in Taiwan. 36.3% of Taiwan identifiers could accept the idea of “one China with different interpretations” in dealing with the mainland, and only 46.5% of them disagreed. In other words, only about one-thirds of all interviewees (45.1% X 67.4% = 30.4%) identify themselves as Taiwanese and understand the concept from blood or historical and cultural aspects. Among this group of people, 38.2% preferred instant or later independence in the SJTU October 2014 survey.10 It seems reasonable to regard 11.6% of people (67.4%×45.1%×38.2% = 11.6%) in Taiwan as core elements of Taiwanese nationalists. However, 16.8% of this small group of people can still accept unification with the Mainland under favorable conditions (democracy). People who identified as Taiwanese seemed to have a clearer understanding of the national identity issue from political/civil/state aspects. For example, 77.3% of them disagreed that the people of the Republic of China (ROC) were also Chinese, even when they were reminded that China could be the short name of the ROC (zhongguo as the short name of zhonghua minguo), and only 15% of them agreed that people living in the ROC were also Chinese. Moreover, 79% of 7 Liu Yi-chou, “National Identity of People in Taiwan—A New Measurement Way,” Paper delivered at the 1998 annual meeting of Association of Chinese Political Science (Taiwan), January 14, 1998, Taipei. 8 Chiang Yi-hua, Liberalism, Nationalism and National Identity (Taipei: Yangchi Cultural Press, 1998), 217-222. 9 Yang Zhong & Yana Zuo, “Explaining National Identity Shift in Taiwan” (Manuscript). 10 Database of Center for Taiwan Studies, Shanghai Jiao Tong University

them agreed to use the name of Taiwan to replace the name of the ROC in the international stages, while only 13.6%of them disagreed;80.9%of them thought that the territory of the ROC should not include the mainland,and only 9.1%of them thought it should include.Finally,only 6.8%of them had more or less unification inclination when making a choice among seven options mentioned above.Although 27.6%of them supported unification with the mainland if the latter had the same political system like Taiwan,61%of them disagreed.The degree of opposition was much stronger than support. In a nutshell,the majority people in Taiwan do not want to unify with the mainland even under their perceived favorable condition (practicing Taiwan-like democracy)and can accept independence under peaceful precondition without committing themselves to "unconditional independence"goal."Unconditional independence"refers to those people who preferred instant or later independence.This suggests the nuance between Taiwanese political identity (citizenship) and policy preference,which is conditioned by Beijing's strong opposition to Taiwanese de jure independence.Indeed,national identity cannot be considered in isolation from its political consequences.Taiwan's"quest"for national identity,therefore,is an open-ended question.2 Taiwan in China's National Identity Reconstruction The Mainland Chinese government is obviously worried that most people in Taiwan identifying themselves as Taiwanese and preferring independence could seriously undermine the prospect of unification in the future.Since the return of Hong Kong and Macau to the motherland, Taiwan's final unification with the Mainland has become even more important for China's rejuvenation.This does not mean Taiwan is the last lost territory to be recovered by the motherland,thus ending its century-old national humiliation by foreign powers.Rather,from Beijing's perspective,the issue of territory recovery was long resolved after the World War II.As Chinese leader Hu Jintao once claimed: Although the mainland and Taiwan have not yet been reunited since 1949,the circumstances per se do not denote a state of partition of Chinese territory and sovereignty.Rather,it is merely a state of political antagonism that is a legacy- albeit a lingering one-of the Chinese civil war waged in the mid-to late-1940s. Nevertheless,this does not alter the fact that both the mainland and Taiwan belong to one China.For the two sides of the Strait,to return to unity is not a recreation of sovereignty or territory,but an end to political antagonism.13 From this perspective,separatists in Taiwan are similar to those in Tibet and Xinjiang,even though Tibet and Xinjiang are already under the PRC's control and Taiwan is yet to be unified.To maintain national sovereignty and territorial integrity,Beijing has pragmatically combined these three regions together in her agenda of enhancing national identity.In recent years,Chinese academia has proposed to reshape their country's national identity in the new era by strengthening u Ibid. 1Lowell Dittmer,"Taiwan and the Issue of National Identity,"Asia Survey,Vol.44,Issue 4,477. i Hu Jintao,"Let Us Join Hands to Promote the Peaceful Development of Cross-Straits Relations and Strive with a United Resolve for the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation,"Speech at the Forum Marking the 30h Anniversary of the Issuance of the Message to Compatriots in Taiwan,December 31,2009. 8

8 them agreed to use the name of Taiwan to replace the name of the ROC in the international stages, while only 13.6% of them disagreed; 80.9% of them thought that the territory of the ROC should not include the mainland, and only 9.1% of them thought it should include. Finally, only 6.8% of them had more or less unification inclination when making a choice among seven options mentioned above. Although 27.6% of them supported unification with the mainland if the latter had the same political system like Taiwan, 61% of them disagreed. The degree of opposition was much stronger than support.11 In a nutshell, the majority people in Taiwan do not want to unify with the mainland even under their perceived favorable condition (practicing Taiwan-like democracy) and can accept independence under peaceful precondition without committing themselves to “unconditional independence” goal. “Unconditional independence” refers to those people who preferred instant or later independence. This suggests the nuance between Taiwanese political identity (citizenship) and policy preference, which is conditioned by Beijing’s strong opposition to Taiwanese de jure independence. Indeed, national identity cannot be considered in isolation from its political consequences. Taiwan’s “quest” for national identity, therefore, is an open-ended question.12 Taiwan in China’s National Identity Reconstruction The Mainland Chinese government is obviously worried that most people in Taiwan identifying themselves as Taiwanese and preferring independence could seriously undermine the prospect of unification in the future. Since the return of Hong Kong and Macau to the motherland, Taiwan’s final unification with the Mainland has become even more important for China’s rejuvenation. This does not mean Taiwan is the last lost territory to be recovered by the motherland, thus ending its century-old national humiliation by foreign powers. Rather, from Beijing’s perspective, the issue of territory recovery was long resolved after the World War II. As Chinese leader Hu Jintao once claimed: Although the mainland and Taiwan have not yet been reunited since 1949, the circumstances per se do not denote a state of partition of Chinese territory and sovereignty. Rather, it is merely a state of political antagonism that is a legacy – albeit a lingering one – of the Chinese civil war waged in the mid- to late-1940s. Nevertheless, this does not alter the fact that both the mainland and Taiwan belong to one China. For the two sides of the Strait, to return to unity is not a recreation of sovereignty or territory, but an end to political antagonism.13 From this perspective, separatists in Taiwan are similar to those in Tibet and Xinjiang, even though Tibet and Xinjiang are already under the PRC’s control and Taiwan is yet to be unified. To maintain national sovereignty and territorial integrity, Beijing has pragmatically combined these three regions together in her agenda of enhancing national identity. In recent years, Chinese academia has proposed to reshape their country’s national identity in the new era by strengthening 11 Ibid. 12 Lowell Dittmer, “Taiwan and the Issue of National Identity,” Asia Survey, Vol. 44, Issue 4, 477. 13 Hu Jintao, “Let Us Join Hands to Promote the Peaceful Development of Cross-Straits Relations and Strive with a United Resolve for the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation,” Speech at the Forum Marking the 30 th Anniversary of the Issuance of the Message to Compatriots in Taiwan, December 31, 2009

institution building,good governance and democratic progress.He Donghang and Xie Weimin point out the problem in the process of China's national identification:the development of civil identity has fell behind that of ethnic identity.4 According to Yao Dali,it is important to speed up political democratization in order to cultivate and consolidate national identity in a multi-ethnic country like China.For Yao,the ideas of sovereignty and equality among people of different strata are the spirit of modern nation-state and also the basic principle of democracy.5 Jin Taijun and Mi Jing argue that political ideas such as democracy,freedom and human rights,as well as institutions based on them are most important to national identity,particularly to a country with diversified identities and multiple belongings of individuals,which is a product of globalization.6 Lin Shangli agrees that the most fundamental dimension of national identity is identification with state institutions,which have decisive significance for building modern countries.Democracy is the political foundation of national identity in modern society.7 In the case of Taiwan,however,political discourse in the mainland has focused more on cultural similarities and ethnic equivalence of people between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, and less on the so-called institutional identification(zhidu rentong).Obviously,this is because the Taiwanese population is predominantly Han Chinese(except for a tiny portion of aboriginals),and Beijing's unification formula is "one country,two systems."Cultural exchanges between the two sides,therefore,were proposed by Beijing as early as 1979.Beijing's open-door policy and peaceful unification appeal to the island,plus Taipei's decision in 1987 to allow cross-strait family reunions for old soldiers who had followed Chiang to Taiwan in the late 1940s have encouraged more people-to-people exchanges between the two sides based on their family ties,hometown connection and ethnic feelings,in addition to business purposes.From ethnic and cultural perspectives,former PRC Chairman Yang Shangkun proclaimed in 1987 that Taiwanese authorities should respect Chinese "overall national interest"(minzu dayi)and have peace talks with Beijing on the unification matter,and former PRC Chairman Jiang Zemin considered Chinese culture as the important foundation for peaceful unification with Taiwan in his 1995 "eight points"remarks.It is worthy to point out that Taiwanese leader Lee Teng-hui responded immediately then by saying that cross-strait exchanges could be based on the foundation of Chinese culture.Many people in Taiwan,including some supporters of the pro-independent DPP, even claimed that Chinese culture was better preserved on the island than in the mainland,as Taiwan has been free of the anti-tradition May 4th movement and Cultural Revolution on the other side of the strait.Despite Taipei's de-sinicization activities under the DPP administration,Beijing has still regarded Chinese culture as the spiritual tie across the strait.Cultural exchanges have made great progress since the KMT came back to power in 2008.As Liu Xiangping argues, cultural identity is one of the basic elements in national identity,followed by ethnic identity (minzhu rentong)and state identity (guojia rentong).In terms of cultural identity,the two sides have more homogeneity than heterogeneity.In terms of state identity,the gap between the two 14 He Donghang&Xie Weimin,"Process of Chinese National Identity and Its Constraining Factors"(zhongguo 含g9 Da enu hne(r论Chen8品mn eds.,Yuanda,No.17 (Beijing:Capital Normal University Press,2012),147. Jin Taijun and Mi Jing,"Reconstruction of National Identity under the Background of Globalization:From the Perspective of Territory Disputes"(cong lingtu fenzhen kan quanqiuhua Beijingxia guojia rentong chonggou), Jianghai Xuekan,2013,No.4,113-114. Lin Shangli,"The Political Logic of Identity Construction of Modem State"(xiandai guojia rentong jiangou de zhengzhi luoji),Chinese Social Sciences (zhongguo shehui kexue),2013,No.8,27-28. 9

9 institution building, good governance and democratic progress. He Donghang and Xie Weimin point out the problem in the process of China’s national identification: the development of civil identity has fell behind that of ethnic identity.14 According to Yao Dali, it is important to speed up political democratization in order to cultivate and consolidate national identity in a multi-ethnic country like China. For Yao, the ideas of sovereignty and equality among people of different strata are the spirit of modern nation-state and also the basic principle of democracy.15 Jin Taijun and Mi Jing argue that political ideas such as democracy, freedom and human rights, as well as institutions based on them are most important to national identity, particularly to a country with diversified identities and multiple belongings of individuals, which is a product of globalization.16 Lin Shangli agrees that the most fundamental dimension of national identity is identification with state institutions, which have decisive significance for building modern countries. Democracy is the political foundation of national identity in modern society.17 In the case of Taiwan, however, political discourse in the mainland has focused more on cultural similarities and ethnic equivalence of people between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, and less on the so-called institutional identification (zhidu rentong). Obviously, this is because the Taiwanese population is predominantly Han Chinese (except for a tiny portion of aboriginals), and Beijing’s unification formula is “one country, two systems.” Cultural exchanges between the two sides, therefore, were proposed by Beijing as early as 1979. Beijing’s open-door policy and peaceful unification appeal to the island, plus Taipei’s decision in 1987 to allow cross-strait family reunions for old soldiers who had followed Chiang to Taiwan in the late 1940s have encouraged more people-to-people exchanges between the two sides based on their family ties, hometown connection and ethnic feelings, in addition to business purposes. From ethnic and cultural perspectives, former PRC Chairman Yang Shangkun proclaimed in 1987 that Taiwanese authorities should respect Chinese “overall national interest” (minzu dayi) and have peace talks with Beijing on the unification matter, and former PRC Chairman Jiang Zemin considered Chinese culture as the important foundation for peaceful unification with Taiwan in his 1995 “eight points” remarks. It is worthy to point out that Taiwanese leader Lee Teng-hui responded immediately then by saying that cross-strait exchanges could be based on the foundation of Chinese culture. Many people in Taiwan, including some supporters of the pro-independent DPP, even claimed that Chinese culture was better preserved on the island than in the mainland, as Taiwan has been free of the anti-tradition May 4th movement and Cultural Revolution on the other side of the strait. Despite Taipei’s de-sinicization activities under the DPP administration, Beijing has still regarded Chinese culture as the spiritual tie across the strait. Cultural exchanges have made great progress since the KMT came back to power in 2008. As Liu Xiangping argues, cultural identity is one of the basic elements in national identity, followed by ethnic identity (minzhu rentong) and state identity (guojia rentong). In terms of cultural identity, the two sides have more homogeneity than heterogeneity. In terms of state identity, the gap between the two 14 He Donghang & Xie Weimin, “Process of Chinese National Identity and Its Constraining Factors” (zhongguo guojia rentong de licheng yu zhiyue yinsu), Marxism and Reality (makesi zhiyi yu xianshi), 2012, No. 4, 16. 15 Yao Dali, “National Identity in Change” (biandongzhong de guojia rentong), in Chen Ming and Zhu Hanmin, eds., Yuanda, No.17(Beijing: Capital Normal University Press, 2012), 147. 16 Jin Taijun and Mi Jing, “Reconstruction of National Identity under the Background of Globalization: From the Perspective of Territory Disputes” (cong lingtu fenzhen kan quanqiuhua Beijingxia guojia rentong chonggou), Jianghai Xuekan, 2013, No. 4, 113-114. 17 Lin Shangli, “The Political Logic of Identity Construction of Modern State” (xiandai guojia rentong jiangou de zhengzhi luoji), Chinese Social Sciences (zhongguo shehui kexue), 2013, No. 8, 27-28

sides has been enlarged.18 Common historical memory is an important factor in shaping national identity.In recent years,mainland media and academic discourse have demonstrated the common efforts of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)and the KMT at fighting against the Japanese invasion back in the 1930s and 1940s,as were shown in various movies,films,newspapers,journals,etc.In particular,Tengchong,a frontier in southwest China and famous battleground between Japanese troops on the one side and KMT military with US aid on the other,has become a popular meeting place for holding academic conferences with scholars from Taiwan participating,including some from the Green camp.The Mainland's intention is clearly to build up common historical memory with Taiwan,even though young Taiwanese without connection with the old KMT regime may feel that historical events in Tengchong are irrelevant to them.From the same purpose,the aboriginal Wushe Uprising against the Japanese colonial rule during 1930s was highly appreciated by the Mainland to highlight the common fate of the two sides during a miserable period of Chinese history.Indeed,Japan's brutal crackdown of the aboriginal uprising and its massacre in Nanjing occurred in the same decade across the Taiwan Strait.Historical memories,in addition to cultural similarities and ethnic equivalence,have been employed by Beijing to retrospectively consolidate the ideational framework of"a community for two-shores'shared fortune." Prospectively,economic exchanges and integration between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait are helpful to enhance national identity.According to neo-liberal or neo-functional assumptions,economic integration will eventually lead to political accommodation and even political integration as the experience of European Union has suggested.At least,the growing functional interdependency,according to Karl Wolfgang Deutsch's concept of a "security community,"will make war too mutually costly to be feasible.Business exchanges between the two sides have evolved from an indirect format in 1980s to a direct and comprehensive way nowadays,particularly since 2008.For example,cross-trade increased from $129 billion in 2008 to $197 billion in 2013,accounting for 29.5%of Taiwan's total foreign trade.Taiwanese direct investment to the mainland approved by the island's authorities increased from $10.7 billion in 2008 to $19.8 billion in 2012.Tourists from Taiwan to the mainland increased from 4.39 million person/times in 2008 to 5.34 million in 2012,while tourists from the mainland to Taiwan jumped from less than 300,000 to 2.54 million during the same period.19 This development has created a sort of"linkage communities"(liansuo shegun)between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait,as Wei Yong pointed out one decade ago.20 During the 2012 elections in Taiwan,a number of big entrepreneurs stood out to support the KMT idea of"one China with different interpretations," which is close to Beijing's one-China principle but different from the DPP's "state-to-state" position.On the other hand,most Taiwanese people have arguably not received direct benefits from the increasing economic integration process.Despite Beijing's "benefit-offering"(rangli) policy in Strait negotiation on economic affairs,including the signing of the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement"and "Service Trade Agreement,"ordinary people in Taiwan have not too much feeling about the utilities of strait exchange on economic revival on the island sLiu Xiangping."A Study on Basic Elements of Cross-Strait Identification and Approaches to Reach the Goal" (laingan rentong zhi jiben yaosu jiqi dacheng lujing taoxi),Taiwan Yanjiu,2011,No.1,1-6. 19 Su Chi,"The General Situation and Prospects of Cross-Strait Relation during Ma Administration"[ma zhengfi shiqi liangan guanxi de gaikuang he zhanwang],in Opportunities and Challenges for Cross-Strait Relations [liangan guanxi de jiyu yu tiaozhan](Taipei:Wunan Press,2013),8. Yung Wei,Toward'Intra-National Union':Theoretical Models on Cross-Taiwan Strait Interactions," Mainland China Studies,Vol.45,No.5 (September/October 2002),23. 10

10 sides has been enlarged.18 Common historical memory is an important factor in shaping national identity. In recent years, mainland media and academic discourse have demonstrated the common efforts of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the KMT at fighting against the Japanese invasion back in the 1930s and 1940s, as were shown in various movies, films, newspapers, journals, etc. In particular, Tengchong, a frontier in southwest China and famous battleground between Japanese troops on the one side and KMT military with US aid on the other, has become a popular meeting place for holding academic conferences with scholars from Taiwan participating, including some from the Green camp. The Mainland’s intention is clearly to build up common historical memory with Taiwan, even though young Taiwanese without connection with the old KMT regime may feel that historical events in Tengchong are irrelevant to them. From the same purpose, the aboriginal Wushe Uprising against the Japanese colonial rule during 1930s was highly appreciated by the Mainland to highlight the common fate of the two sides during a miserable period of Chinese history. Indeed, Japan’s brutal crackdown of the aboriginal uprising and its massacre in Nanjing occurred in the same decade across the Taiwan Strait. Historical memories, in addition to cultural similarities and ethnic equivalence, have been employed by Beijing to retrospectively consolidate the ideational framework of “a community for two-shores’shared fortune.” Prospectively, economic exchanges and integration between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait are helpful to enhance national identity. According to neo-liberal or neo-functional assumptions, economic integration will eventually lead to political accommodation and even political integration as the experience of European Union has suggested. At least, the growing functional interdependency, according to Karl Wolfgang Deutsch’s concept of a “security community,” will make war too mutually costly to be feasible. Business exchanges between the two sides have evolved from an indirect format in 1980s to a direct and comprehensive way nowadays, particularly since 2008. For example, cross-trade increased from $129 billion in 2008 to $197 billion in 2013, accounting for 29.5% of Taiwan’s total foreign trade. Taiwanese direct investment to the mainland approved by the island’s authorities increased from $10.7 billion in 2008 to $19.8 billion in 2012. Tourists from Taiwan to the mainland increased from 4.39 million person/times in 2008 to 5.34 million in 2012, while tourists from the mainland to Taiwan jumped from less than 300,000 to 2.54 million during the same period.19 This development has created a sort of “linkage communities” (liansuo shequn) between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait, as Wei Yong pointed out one decade ago.20 During the 2012 elections in Taiwan, a number of big entrepreneurs stood out to support the KMT idea of “one China with different interpretations,” which is close to Beijing’s one-China principle but different from the DPP’s “state-to-state” position. On the other hand, most Taiwanese people have arguably not received direct benefits from the increasing economic integration process. Despite Beijing’s “benefit-offering” (rangli) policy in Strait negotiation on economic affairs, including the signing of the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement” and “Service Trade Agreement,” ordinary people in Taiwan have not too much feeling about the utilities of strait exchange on economic revival on the island 18 Liu Xiangping, “A Study on Basic Elements of Cross-Strait Identification and Approaches to Reach the Goal” (laingan rentong zhi jiben yaosu jiqi dacheng lujing taoxi), Taiwan Yanjiu, 2011, No. 1, 1-6. 19 Su Chi, “The General Situation and Prospects of Cross-Strait Relation during Ma Administration” [ma zhengfu shiqi liangan guanxi de gaikuang he zhanwang], in Opportunities and Challenges for Cross-Strait Relations [liangan guanxi de jiyu yu tiaozhan] (Taipei: Wunan Press, 2013), 8. 20 Yung Wei, “Toward ‘Intra-National Union’: Theoretical Models on Cross-Taiwan Strait Interactions,” Mainland China Studies, Vol. 45, No. 5 (September/October 2002), 23