CANCER CLINICS Clinie on Bone Tumors DR.JAFFE: For the ake uss fully even the first of ih cate up of primary lesi by Iwe one with the mind a very ger ral orienting clas Case1 pigeonholimg DR.MILGRAM:The patient in the case into a few d prev any majo Tumors developing as primary lesions in sharp pa Tumors invading bones from overlying rouble had

c@a @U@tt@ @ .,@ @@Iui Clinic on Bone Tumors DR. JAFFE: For the sake of general orientation, it seems worth remarking that the tumors of bones make up a large and intriguing group of lesions. In the clinical investigation of them, the disci plines of surgery, pathology, and roent genology converge and reinforce each other—perhaps more strikingly than in most other fields of medical practice. In view of the variety of tumors that one encounters in connection with the bones, it seems advisable first to have in mind a very general orienting classifica tion of them, such as is presented here. This allows for the easy pigeonholing of all the possible bone tumors into a few very general categories. General Classification of Tumors of Bones Tumors developing as primary lesions in bones Tumors invading bones from overlying soft parts Tumors metastatic to bones Tumors developing at sites of pre-existing bone disease Tumors developing at sites of damage to bone from noxious agents In a clinic such as we are presenting here, it would obviously be impossible to discuss fully even the first of these cate gories—that is, the tumors developing as primary lesions in bones. We are limiting ourselves to the presentation of the clini cal (including surgical), pathological, and roentgenographic problems raised by two cases: one of giant-cell tumor of the upper end of a tibia and one of chondrosarcoma of the lower end of a femur. Case 1 DR. MILGRAM: The patient in the case of giant-cell tumor of the tibia was a woman of 58 who entered the hospital complaining of difficulty with the right knee, of six months' standing, but who had previously never suffered any major illness. The difficulty had started with sharp pain over the inner aspect of the knee. The patient limped for several weeks, but the trouble had subsided to dull aching and discomfort, apparently associated with slight temporary loss of From time Hospital for Joint Diseases, New York, New York. 28

attcni rom a sm ragn this the of th the r he ould be taken unde t tha surgery DR.JAFFE:I am certain that we will,in FIGURE

weight, by the time a roentgenogram was taken and the patient referred to us. Physi cal examination revealed slight atrophy of the thigh and increased local temperature over the front of the knee region but no restriction of motion of the knee on the affected side. Around the tibial tubercle there was a fluctuant, nonpulsating mass, about 1½in. in diameter, over which the skin was not fixed. Tenderness extended from this area to the tibial margin of the knee joint, along the inner side. There were no masses in the groin, and the rest of the examination revealed no abnor mality. Roentgenograms of the affected knee area were taken, and I would like to ask for comment on them. DR. POMERANZ: As Fig. 1 shows, there is a large, osteolytic lesion in the proximal extremity of the tibia. On the inner aspect of the shaft, the cortex has been thinned, and, for some distance below the articu lar surface medially, the contour of the bone is bulged. Laterally, the lesional area extends into the external condyle of the tibia, leaving only a small area of it intact. Superiorly, the lesional area reaches to the articular surface in the region of the medial condyle. In favor of a diagnosis of giant-cell tumor in this case is the age of the patient (more than 20), the precise location of the lesion in the affected bone (that is, in the end of the bone and the adjacent meta physis), and the general roentgeno graphic appearance of the lesional area. However, one does sometimes encounter a lesion meeting all these criteria that may still not be a giant-cell tumor. For in stance, if located in the area in question here, a fibrosarcoma of bone, a focus of metastatic cancer, or a focus of so-called plasmacytoma occasionally raises the question of differential diagnosis from giant-cell tumor. In any event, in connec tion with a lesion such as we have in this case, though there is strong presumptive evidence in favor of the diagnosis of giant cell tumor of bone, it seems advisable that that diagnosis be supported by study of biopsy material and that definitive surgery he guided by the histological findings. DR. JAFFE: I am certain that we will, in this case, be able to establish, at the time of the operative intervention, a definitive diagnosis from a small fragment of tissue removed from biopsy. In other words, I think it is perfectly safe in this case to proceed with any definitive surgical pro cedure contemplated, on the basis of the report from an open biopsy specimen sub jected to frozen section. One may ask, in this connection, whether a needle biopsy, made some days in advance of the contemplated interven tion, might be preferable to the open biopsy at the time of the intervention. My answer to that would be “¿no.― In the first place, while a needle biopsy might supply sufficient tissue to make the correct diag nosis possible, it would not furnish enough detail and context to satisfy me in regard to the histological detail of the lesion, whether it be a giant-cell tumor or not. In the second place, since we strongly sus pect, on clinical and roentgenographic grounds, that the lesion is a giant-cell tu mor, there does not seem to be much risk in doing an open biopsy, especially since the biopsy specimen would be taken under tourniquet protection. FIGURE 1 29�

DR.MILGRAM:Tissue for the biopsy radiaion therapy has the icinity tib tubercl nd the idity but it is th form of the rily pre e d ity of the he tib his know se we do for the urgi of the paticnt'sm er.befo forest Isarcom the rem the tumor that it ma can be h in plast nent of or the nt-cell on, re that ne apy ds exp ed in the) migh ture is ncl in th his and a half vea follow bea ent has cure of the iaw bones h ell tu not sur vith are ranulomas of for co on in p Case 2 hi alone. DR.MILGRAM We proceed now a an 37 v s in a sure in of th feel dually chan to on hle sites the ent note end the bones (fem ur. Neither the There is another e of -cell ign e full n the y and lowe knee hat more are radio nd radic ble.Thei on.the low of the tion tment she e primarily by irr ately but diffu sely tender. specially medi

DR. MILGRAM: Tissue for the biopsy was removed from the fluctuant mass in the vicinity of the tibial tubercle, and the diagnosis of giant-cell tumor was con firmed by the pathologist. The definitive surgical procedure consisted of unroofing the upper 3 in. of the shaft of the tibia, removing all of the tumor tissue present, and implanting cortical and cancellous bone obtained from the posterior aspect of the patient's ilium. However, before the bone grafts were inserted, the wall of the cavity left after removal of the tumor tis sue was cauterized with a 50 per cent zinc chloride solution. At the termination of the surgical procedure, the limb was im mobilized in plaster. In carrying out the surgical procedure in question, we were fully aware that, despite our effort to eradicate the lesion by local resection, a recurrence might, nevertheless, take place. Fortunately, in this case, a five and a half year follow-up showed that there was no recurrence, and the patient has been cured of her tumor and left with little or no functional dis ability. However, there are those who maintain that giant-cell tumor might well be treated with roentgen-ray therapy, with out surgical intervention at all. 1 would like to ask for comment on this point. DR. FRIEDMAN: In regard to irradiation I believe that a certain percentage of giant cell tumors of bone can be arrested by this procedure alone. However, in prin ciple, I advocate irradiation instead of surgery for giant-cell tumor only as a second choice. Specifically, I advocate it if the tumor is in a surgically inaccessible site or if it is so large that its removal would entail a serious mutilation of the part. However, giant-cell tumors in surgi cally inaccessible sites are rare in com parison to those occurring for instance at the ends of the predilected bones (femur, tibia, radius, and humerus). There is another category of giant-cell tumor occurring in children and adoles cents. These occur in the upper and lower jaws and in the flat bones. These lesions are radiosensitive and radiocurable. Their treatment should be primarily by irradia tion. DR. JAFFE: Irradiation therapy has the obvious advantage of avoiding surgical morbidity but it is the slowest form of therapy. Furthermore, it does not neces sarily prevent severe deformity of the part. In regard to the cases seemingly cured by this method alone, we do not yet know so much about the likelihood of recurrence as we do for the cases treated surgically. We do know that radiotherapy may not forestall the occasional sarcomatous trans formation of the lesion, and there is rea son to suspect that it may sometimes even be a factor in eventually bringing this about. Finally, there can be little doubt that much of the enthusiasm for the treat ment of giant-cell tumor by irradiation therapy (in preference to surgery) that one finds expressed in the older, and to a lesser degree in the current, medical liter ature is influenced by inclusion in the sta tistics of many cases in which the diag nosis of giant-cell tumor would not bear detailed scrutiny. In fact, those “¿giant-cell tumors of the jaw bones― to which Dr. Friedman refers are actually not giant cell tumors at all. It is not surprising that they yield so readily to irradiation, for they are reparative granulomas of the jaw bones, containing sparse numbers of giant cells. They also heal readily when curetted. Case 2 DR. MILGRAM: We proceed now to the case of the chondrosarcoma of the femur. The patient was a woman 37 years of age. Her disability, of three months' standing, had begun as a “¿heavyfeeling― in the left thigh, just above the knee, and this feeling gradually changed to one of pain. Furthermore, a month before her first visit, the patient noted a tender spot above and to the outer side of her left kneecap. Neither the personal history nor the physical examination revealed any thing significant, save for some fullness of the lower third of the left thigh, extending down about the knee, somewhat more marked laterally than medially. On palpa tion, the lower 6 in. of the shaft of the femur was found thickened and moder ately but diffusely tender, especially medi 30��

in the groin. r a slig scrum-alka Ycenmtalcaniagtinou ortio hem even a benign ignancy which viab FIGURE 2 tilag tra ign rlying sof 1s0 and. and pr in s ma forr is pro malignant gra crit or benignancy (Fig comment along these femoral shaf the DR.P nterol terall or and med cartilage tumors of bone may be sum- lating new-bone deposition on the cortex 31

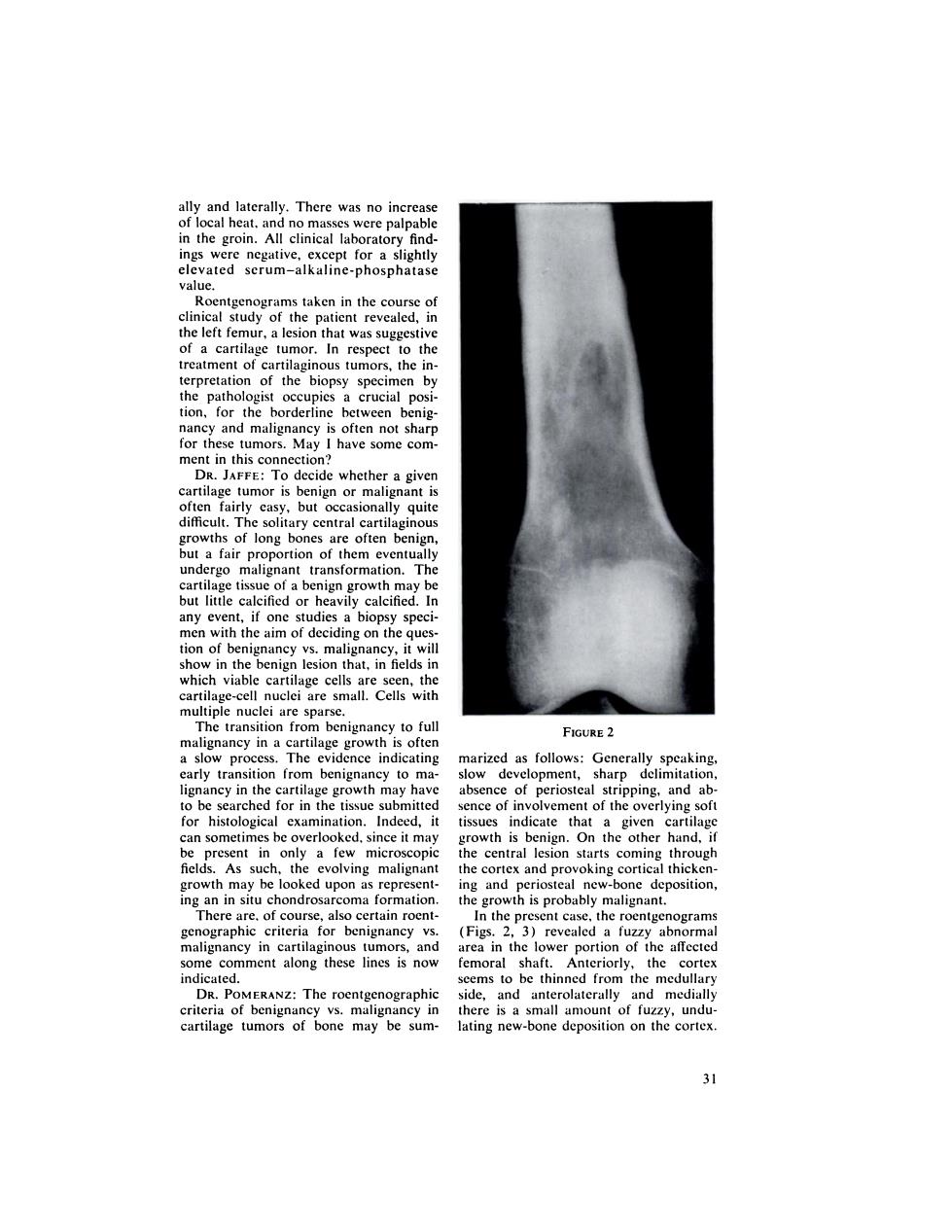

ally and laterally. There was no increase of local heat, and no masses were palpable in the groin. All clinical laboratory find ings were negative, except for a slightly elevated serum—alkaline-phosphatase value. Roentgenograms taken in the course of clinical study of the patient revealed, in the left femur, a lesion that was suggestive of a cartilage tumor. In respect to the treatment of cartilaginous tumors, the in terpretation of the biopsy specimen by the pathologist occupies a crucial posi tion, for the borderline between benig nancy and malignancy is often not sharp for these tumors. May I have some com ment in this connection? DR. JAFFE: To decide whether a given cartilage tumor is benign or malignant is often fairly easy, but occasionally quite difficult. The solitary central cartilaginous growths of long bones are often benign, but a fair proportion of them eventually undergo malignant transformation. The cartilage tissue of a benign growth may be but little calcified or heavily calcified. In any event, if one studies a biopsy speci men with the aim of deciding on the ques tion of benignancy vs. malignancy, it will show in the benign lesion that, in fields in which viable cartilage cells are seen, the cartilage-cell nuclei are small. Cells with multiple nuclei are sparse. The transition from benignancy to full malignancy in a cartilage growth is often a slow process. The evidence indicating early transition from benignancy to ma lignancy in the cartilage growth may have to be searched for in the tissue submitted for histological examination. Indeed, it can sometimes be overlooked, since it may be present in only a few microscopic fields. As such, the evolving malignant growth may be looked upon as represent ing an in situ chondrosarcoma formation. There are, of course, also certain roent genographic criteria for benignancy vs. malignancy in cartilaginous tumors, and some comment along these lines is now indicated. DR. POMERANZ: The roentgenographic criteria of benignancy vs. malignancy in cartilage tumors of bone may be sum FIGURE 2 marized as follows: Generally speaking, slow development, sharp delimitation, absence of periosteal stripping, and ab sence of involvement of the overlying soft tissues indicate that a given cartilage growth is benign. On the other hand, if the central lesion starts coming through the cortex and provoking cortical thicken ing and periosteal new-bone deposition, the growth is probably malignant. In the present case, the roentgenograms (Figs. 2, 3) revealed a fuzzy abnormal area in the lower portion of the affected femoral shaft. Anteriorly, the cortex seems to be thinned from the medullary side, and anterolaterally and medially there is a small amount of fuzzy, undu lating new-bone deposition on the cortex. 31

RmpbadcedontceLnurelecandaeeiC cartilage growth in dvisabl hip th troubled by phan (for nine days)of 2 per ine ints heD2pe the was walkin her return ho she Its use was a revel he of he of her help FIGURE 3 ars afte 二 on the basis we shoul he From a practica vascular ound to the h cy. employed only for metastasis located as to b

many had double nuclei, and some few had bizarre nuclei. These findings indi cated to him that the cartilage growth in question was a chondrosarcoma. Since we had no way of knowing how far up into the femur the chondrosarcoma was extending, it was thought advisable to do a disarticulation at the hip joint, rather than an amputation through the femoral shaft. No difficulty was encoun tered in the healing of the incisions, but, after the disarticulation, the patient was troubled by “¿phantomlimb― sensations. These were relieved by periodic injection (for nine days) of 2 per cent procaine into the sympathetic ganglia of L-2. Despite encouragement, the patient could not manage crutches for four weeks, but by the sixth week she was walking well on one crutch and able to ascend and descend stairs. On her return home, an episode of depression occurred, interfer ing with her program of gait training. However, shrinkage of the stump con tinued and she consented, five months after operation, to being fitted with a prosthesis. Its use was a revelation to her, and with her resumption of social life she again took over the reins of her house hold. Seven months after disarticulation. she was quite free of her pain and was doing most of her housework for a family of three, with the help of a younger sister. She was last examined three years after the disarticulation operation. There was no evidence of recurrence locally in the stump or elsewhere. Her health continues normal. Perhaps, before concluding, we should have some comment on the value of roentgen-ray therapy for the cartilage tumors. DR. FRIEDMAN: From a practical clinical point of view, I must say that I have never arrested a chondrosarcoma with irradiation alone. Chondrosarcomas should be treated surgically, and irradia tion be employed only for metastasis or when the primary tumor is so extensive or so unfavorably located as to be moper able. In such cases, irradiation can some times achieve palliative prolongation of comfortable life. FIGURE 3 It is difficult to decide, on the basis of the available roentgenograms, whether this cartilage tumor is benign or malignant. DR. MILGRAM: To establish the diag nosis, a biopsy was done. The periosteum was found diffusely thickened, whitish. and irregular, and soft, gray-white. rather avascular tissue was found to have ex tended through the periosteum on the medial side of the femur, about 3 in. above the median epicondyle. Indeed, in this case, tissue removed at the biopsy posed no problem in regard to the diagnosis of chon d rosarcoma. The pathologist re ported that the cartilage tissue submitted showed considerable cellularity, large lumbers of the cells had plump nuclei, 32�